Categories

Getting ahead of Cholera and Putting Cholera behind

The ‘Great Stink’

The tale of John Snow is famous among epidemiologists. Picture the summer streets of London in 1854: busy, lined with cowsheds, slaughterhouses, and grease-boiling dens. Its sewer system overrun by all sorts of contaminants. The stench is pervasive. Unbearable. To ameliorate it, the government mandates people start dumping their waste into the River Thames. Suddenly, thousands start falling sick with cholera. Hundreds more begin to die, dehydrated, feverish, their beds soaked in bloody diarrhea.

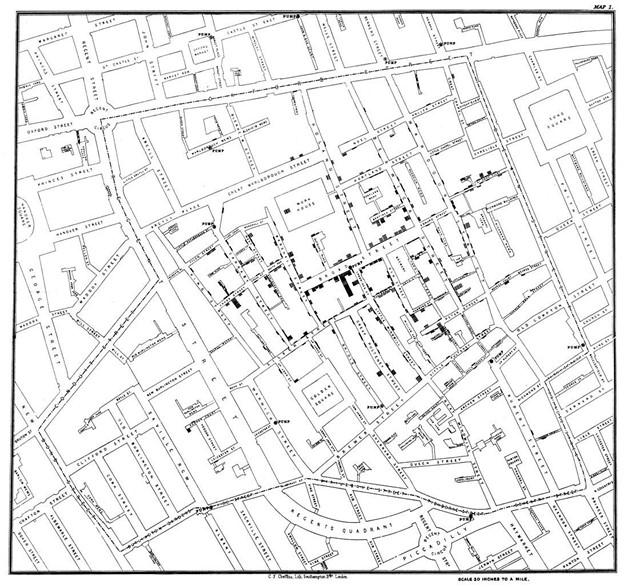

Snow, an obstinate obstetrician, refuses the notion that ‘bad air’ is the culprit of the horrendous outbreak. He maps the homes of sick families and traces the focus of infection with unbelievable accuracy to a sewage point on Broad Street. Yanks the handle off of the water pump, stops the outbreak and wins the argument. It wasn’t ‘bad air’ but ‘bad water’. Not a particle we breathed but, alas, a germ we ingested.

It is mystifying that cholera is still a problem when it is no longer a mystery

Snow’s discovery prompted politicians in 1858 to pass a bill and implement public works to prevent sewage from passing into the River Thames. That alone nearly eliminated the risk of another outbreak in London.

In 1879 Louis Pasteur tested the first cholera vaccines on chicken and other animals. Then, in 1884, Jaume Ferran isolated a vaccine from sick patients in Marseilles that was used to mass inoculate 30,000 people in Spain. Containing an outbreak has been doable since Victorian times. Today we have highly effective oral cholera vaccines (OCVs) and treatments.

Microbiologists in the 20th Century discovered that copepods, small aquatic crustaceans that live in fresh and saltwater, are a major vector and that above-average temperature and rainfall wake up the otherwise quiescent bacteria.

Weather forecasts in the 21st Century are fairly robust at predicting when, where, and how likely a hot period of heavy rain will happen. We have access to epi data and other information on access to safe drinking water, infrastructure, and socioeconomic activity. Poverty, conflict, and exposure to extreme weather events like cyclones and monsoons exacerbate the risk of cholera, especially when people are left with no choice but to interact with contaminated water.

With the knowledge garnered in the last two hundred years, we should have enough tools and strategies to prevent, control, and eliminate a disease that belongs in a library, between voluminous tomes on the Black Death of the 14th Century and the Spanish Flu of the 20th Century. Tragically, this is not the case.

Germs thrive in unresolved socioeconomic inequality, poverty, and conflict

Despite being entirely preventable, cholera is not behind us. A quarter into the 21st Century, it still infects 3 million people and kills 95,000 each year. The burden is greatest in the countries that can least afford it.

Turn your imagination to the war-torn streets of Yemen in the spring of 2017. As busy, as hot, and as contaminated as the streets of Snow’s London. Hospitals have been bombed. Garbage is piling up on the streets. Clean water is scarce. Since the last six months, the country has been riddled with an unrelenting cholera outbreak. 1.2 million are sick; half of them children. 2,500 have died. Burned out nurses and doctors are desperate, chasing the epidemic, trying to manage a multiplying caseload, unequipped, under-resourced. Finally, it is October. Sixteen months have passed since the epidemic broke out. Amid high insecurity and access restrictions, the first doses of oral cholera vaccines (OCV) start to arrive.

War’s end is not in sight. It will take many years to rebuild and recover from the devastation it has caused. In the meantime, cholera remains a threat. Can it be managed better?

Stay ahead of the problem while you can solve it

Fragility, conflict, and protracted humanitarian crises make investing in the type of long-term solutions that are needed far more challenging. This is never an excuse to relinquish our strategic focus on the pursuit of policies and measures that can ultimately put cholera behind us.

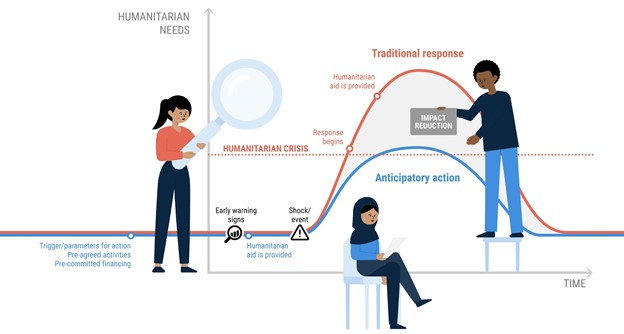

But neither should the fact that in many places these solutions are still out of reach stop us from getting ahead of its worst outcomes. Waiting for cholera cases to grow to react -even when the speed of reaction is fast- just isn’t fast enough. We need to anticipate.

Proof of concept is near

A global coalition of more than fifty international humanitarian practitioners and global experts from the World Health Organization (WHO), UNICEF, the International Organization for Migration (IOM), as well as scientists and researchers from the medical, public health, and climate communities are working to test if anticipatory action can stop an outbreak from becoming a crisis in Yemen, Mozambique, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The pilot initiative, part of a larger portfolio to scale up anticipatory action, is co-sponsored by the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC), the Risk-Informed Early Action Partnership (REAP), the UK Government, and the Red Cross, and financed by the UN Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF).

By the end of 2021, the group aims to put together a mechanism where 1) data, 2) money and 3) actions are pre-arranged to bring forward the response to cholera outbreaks. OCHA calls this an ‘anticipatory action framework’.

1. Triggers

Cholera is a multidimensional phenomenon that affects communities in different ways at different times depending on where they live. Experts are exploring the combined use of existing models, tools, and data, to develop appropriate triggers to act early, when the risk of cholera goes up and before epi curves begin to climb. That includes information on hotspots, human mobility, water and sanitation, conflict, epi data, weather forecasts, operational capacity, etc.

Depending on the place, several risk factors could help determine the likelihood and get ahead of an outbreak:

- Suspected cholera cases before confirmation from the laboratory or reported cases in nearby locations to anticipate preparedness activities and scale up surveillance systems.

- Sudden shocks such as floods, drought or large displacement waves.

- A reduction in vaccine coverage or deteriorating water and sanitation conditions.

- Temperature, rainfall and other predictable environmental factors will provide significant additional lead time and help dynamically target areas at risk, including where to detect contaminated water.

2. Money

If triggers are met in any of the three pilot countries, CERF will release up to US$10 million to UN agencies for the implementation of activities included in pre-agreed plans.

3. Actions

To get ahead of a likely outbreak, as soon as the anticipatory action framework is activated, agencies will:

- Provide hygiene kits; repair and protect water sources; start chlorination; set up hand washing stations; and train and deploy rapid response teams.

- Supply equipment and upgrade laboratories; train lab staff; procure rapid diagnostic tests; assess and strengthen transport systems for sample transportation.

- Develop risk communications and community plans; assess community mobility and places of potential transmission such as markets; and identify best locations for public health community interventions.

- Request, distribute and administer OCV.

- Establish community-based case management capabilities; invest in hygiene measures and waste management in health clinics; procure and preposition supplies, and ensure clinics have access to potable water.

- Coordinate with partners, including ministries of health, to limit duplication and deploy financing and resources as efficiently as possible.

CERF funding is pre-arranged for up to eighteen months from the moment the anticipatory action framework is in place. OCHA is committed to facilitating and sharing the independent impact evaluation of the pilot.

Anticipation and longer-term solutions are both urgent and mutually reinforcing

Climate change is driving up the risk of known communicable diseases breaking out, as well as of new diseases emerging from unknown pathogens.

In the case of cholera, it is essential we accelerate the GTFCC global strategy to reduce deaths by 90% and stop transmission in 20 countries by 2030. This plan is the most comprehensive path to a world where cholera is no longer a threat to public health. It must be supported. While we get there, however, we must acknowledge there will be many more outbreaks in fragile places. It is critically important we get ahead of them if we want to put the disease behind us.

It is a once in a century opportunity.

Juan Chaves-Gonzalez

Humanitarian Financing Strategy Analyst, UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

Visiting Scientist, Harvard Humanitarian Initiative at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health