Categories

How can we expand anticipatory action in conflict settings? Highlights from the Dialogue Platforms

A priority in the Anticipation Hub’s strategy for 2021-24 is to stimulate learning and exchange between practitioners, scientists and policymakers. Such collaboration between partners working across the spectrum of anticipation will improve our understanding of the barriers and potential opportunities for better anticipatory programming.

One way to collaborate is the annual Dialogue Platforms, and a recurring theme in 2021 was how we can expand anticipatory action in conflict settings. During the Dialogue Platforms in Latin American and Caribbean, Africa and Asia-Pacific, colleagues in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Colombia, Honduras, Mali and Sudan shared insights from their work in this field.

Why conflict-affected areas?

People living in fragile or conflict-affected areas are particularly vulnerable to climate shocks and stresses. Conflicts exacerbate their vulnerabilities, leading to a higher risk of exposure and vulnerability to climate hazards. As a result, most deaths from natural disasters occur in conflict areas, largely due to the lack of preparation and adequate coping mechanisms in place. This overlap between climate risks and conflict affects people’s access to basic services, weakens government capacity, increases health disparities, and worsens food security - all of which can fuel humanitarian needs.

Anticipatory action reduces the humanitarian needs of a population and ensures life-saving support reaches those that need it most. It is therefore especially relevant to conflict and displacement contexts. In conflict settings, breakthroughs in anticipatory action demand increased capacity among state and non-state actors, improved facilitation of local expertise, better collaboration with local partners, and a better understanding of the context through enhanced data collection and risk mapping. However, we must acknowledge the additional challenges present in implementing anticipatory action in such complex settings, and ask how we can better prepare for future conflict events.

Build capacity

Improving capacity at all levels provides a strong foundation for the success of anticipatory action programmes. At the Regional Dialogue Platforms in 2021, almost all session leaders and speakers mentioned the need to build capacity to improve the effectiveness of early actions. Others provided examples of how this works in practice. For example, during the last 13 years FAO Colombia has helped over 40,000 families affected by agro-climatic and conflict risks. For these programmes to be successful, they call for increased capacity in risk management at multiple levels, from state institutions and hydro-meteorological services to local community organizations.

FAO Burkina Faso echoed this call to action when detailing the future of anticipation in their work. Anticipating the exact needs of a situation isn’t always possible, but more capable government bodies and better cooperation with humanitarian actors allow for better early responses. Strengthening the capacity of government authorities and local institutions is therefore key to better understanding the context and the needs of the people affected.

Research conducted by Catalina Jaime of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre focused on the availability and communication of weather forecasts to predict climate hazards in conflict settings. Historical analysis of 72 disasters across 20 countries proved that the majority of weather hazards can be forecast with at least 30% probability, and at least three days lead time. In conflict contexts, however, much of this forecasting information is not communicated or stressed in monitoring and reporting. Many of the essential ‘building blocks’ for forecasting and early-warning systems exist, but need to be improved and financed. Recommendations to address this included building the capacity of countries to communicate hydro-meteorological forecasts, especially those concerning food security outlooks in conflict settings; there is also a need for increased investment in extreme temperature forecasting and communication.

One of the primary lessons we are learning, applying and qualifying is how to make comprehensive risk analyses with communities in rural areas where there are permanent pressures due to armed groups, displacement and confinement, and ever-present risks of droughts and floods ... We have adapted to the reality of our programming and work closely with communities on these dual threats.

Local expertise and collaboration

Efforts to increase localization have long been touted as a priority within the humanitarian sector, but taking advantage of local knowledge remains a gap in programming for anticipatory action. Local knowledge is a primary resource for planning and improving anticipatory action, simply because affected people understand their needs and the context better than anyone. There needs to be an emphasis on listening to the experiences of those at the heart of anticipatory action.

At the Latin America and Caribbean Dialogue Platform, Teresa Armijos Burneo from the University of East Anglia presented research on the double risk of displacement and disaster in Colombia. In particular, this research aimed to measure how displaced people interact with multiple forms of risks, as well as the capacity of local communities and the organizations that support them. Barriers to effective anticipation include limited access to high-risk rural areas, and the fact that people fall through the cracks of institutional and legal care. To tackle these challenges, it is necessary to seek out local and indigenous knowledge and cultivate closer connections with community leadership.

Considering anticipatory actions relevant to displaced communities, Sally James from FAO outlined the importance of listening to the lived experience of migrants, refugees and internally displaced persons, as well as their host communities. Nearly 10 million people are displaced in the Asia-Pacific region, and implementing early action means considering the economic, environmental and social impacts of displacement, for both the displaced and the host communities. She stressed the importance of integrating migration and social cohesion indicators as triggers in the planning stages, and collecting and disaggregating data figures.

Similarly, Gado Abdouramane from the Climate Centre spoke about how local communities were involved in planning the Early Action Protocol for Flooding developed by the Mali Red Cross. Inter-community conflicts and food insecurity add complexity to the implementation of successful early responses to riverine floods. Community training and awareness-raising campaigns by Mali Red Cross volunteers were essential for communicating the response plan. Involving communities and volunteers also means that the Mali Red Cross will be able to respond in anticipation of floods - even in contexts complicated by conflict.

Speakers from Red Cross National Societies in Colombia and Honduras pointed to the importance of utilizing local capacity when planning anticipatory actions in complex settings. However, there is a need to recognize how people experience discrimination, exclusion and inequality in communities, and how they are affected by anticipated climate hazards. There must also be translations of early warnings into local languages, and an understanding of the information channels relevant to displaced communities. Community consultations can help in this respect.

Can we anticipate all the needs that arise for displaced people in conflict settings? No. To better anticipate, we need to better know and understand the situation … better understanding will lead to better responses.

Koffy Kouacou, FAO Burkina Faso

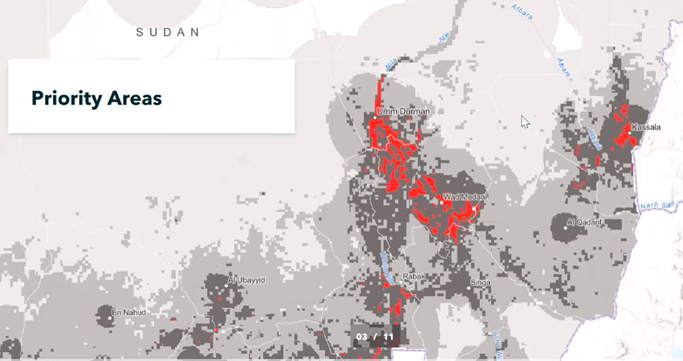

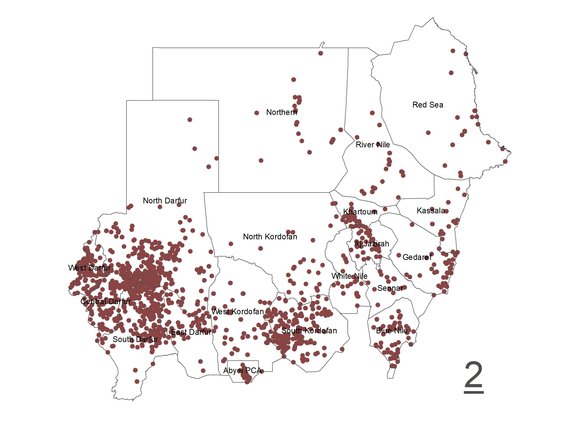

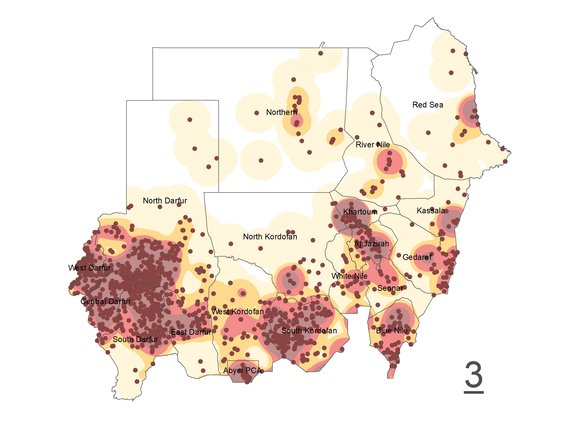

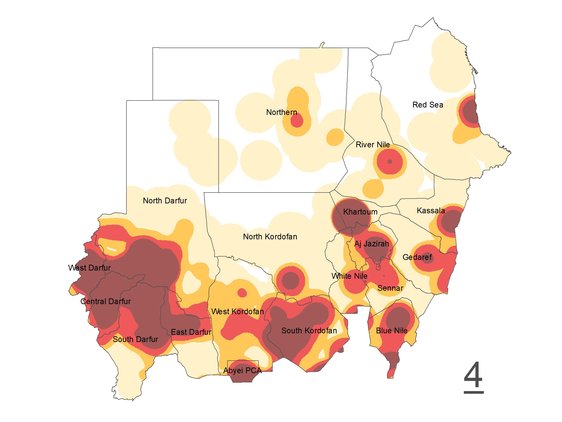

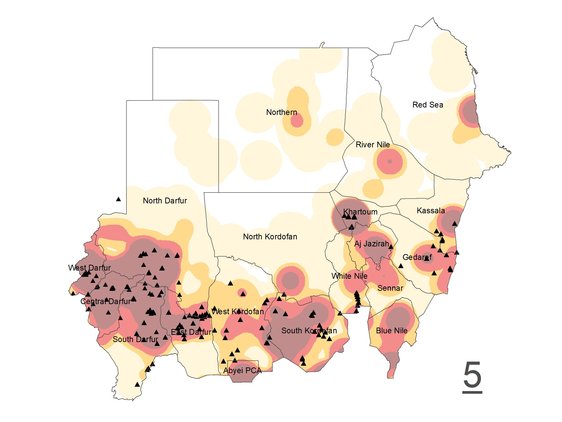

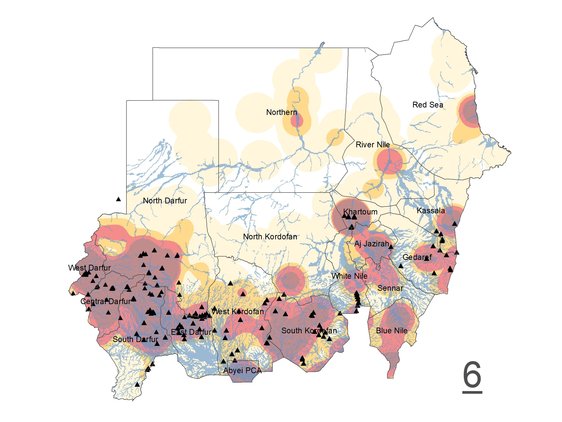

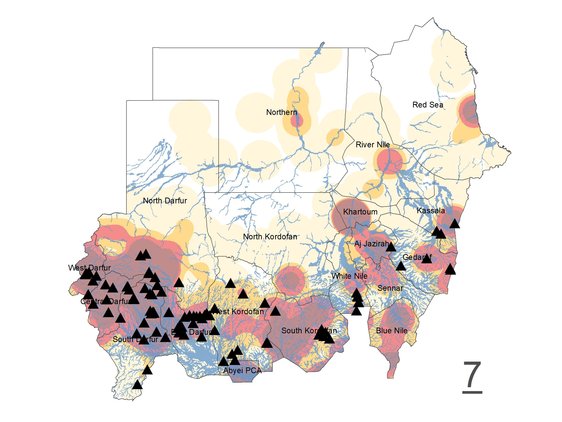

Example of how conflict can exacerbate vulnerabilities

The image gallery below showcases an example of how conflict can exacerbate vulnerabilities. In Sudan conflict has caused a high number of refugees and IDPs to settle within flood areas. People are potentially exposed to floods while at the same time their capacities to mitigate or cope are decreased, increasing their vulnerability, and creating a complex disaster risk setting.

1. Sudan

2. Conflict incidents between 2000 – 2021

3. Density analysis of incident points to identify conflict hot spots

4. Conflict hot spots in Sudan between 2000 – 2021

5. Locations of IDP and refugee camps/settlements

6. Flood areas

7. IDP and refugee camps/settlements located in flood areas

1. Sudan

2. Conflict incidents between 2000 – 2021

3. Density analysis of incident points to identify conflict hot spots

4. Conflict hot spots in Sudan between 2000 – 2021

5. Locations of IDP and refugee camps/settlements

6. Flood areas

7. IDP and refugee camps/settlements located in flood areas

Context is key

Humanitarian actors can only respond to what they understand, so it is essential that organizations have an informed, multi-layered and dynamic view of context: an improved knowledge of the situational environment, and of the specific drivers of conflict and displacement.

At the Africa Dialogue Platform, Koffy Kouacou from FAO Burkina Faso stressed that improved knowledge of the situation, stemming from improved government capacity, should inform the programming of early responses. Understanding context is an ongoing process, though; we need better foundational insights into a situation and the needs of the most vulnerable people, but also a flexible and layered view that can change as rapidly as the situation develops.

A clearer understanding of context is also rooted in improved data collection and mapping tools. Research presented by the Climate Centre has sought to map the multi-layer risks present in Sudan. This helps practitioners to fully grasp the complexity of the interactions between conflict, displacement and natural hazard risks, especially over extended timescales. The results also highlight unmapped hotspots in which future programmes could reach those at the centre of these complex risks. This attempt to visually capture unmapped and highly vulnerable areas provides organizations with better knowledge and contextual information. Using tools like OpenStreetMap and remote data-collection also point to more accessible and locally driven forms of feedback and expertise for context analysis.

However, understanding the context and predicting hazards does not translate easily into effective anticipatory action in highly volatile contexts. Kaustabh Devale from FAO shared some insights into the challenges of working in Afghanistan since the Taliban takeover in August 2021. He noted the economic crisis in the country as a barrier to implementing early actions, as well as the many institutional barriers resulting from huge losses of technical expertise in hydro-meteorological and government positions. Institutional barriers feed into challenges of data assessment and analysis, as the circumstances in the country hamper data collection, access and collaboration.

Questions regarding the terms and principles of engagement for humanitarian actors, given the de facto authorities at national and sub-national levels in Afghanistan, also present practical challenges for anticipatory action. Further complicating the situation is an upcoming La Niña event, which is expected to trigger another drought, potentially leading to a ‘perfect storm’ of food insecurity and decreased livelihood and agricultural production in the face of the ongoing civil unrest and economic crisis.

As improved knowledge does not always lead to better actions, important questions remain. How do we structure these much-needed changes in practice? If we agree on the barriers present and the key steps forward, how do we work towards improving anticipatory action? The next step for the anticipation community is to ask these questions and share breakthroughs and challenges to improve early actions in complex conflict settings.

Get involved

The Anticipatory Action in Conflict Practitioners Group focuses on how we can expand anticipatory action to conflict settings. Further details of how to join this working group are on the Anticipation Hub.

The annual Dialogue Platforms create a space for learning and collaboration, and hopefully answering these essential questions. To join the conversation, sign up for the upcoming virtual Global Dialogue Platform, which kicks off on December 7th, 2021.

You can read more about anticipatory action and conflict on the Anticipation Hub.

Author:

Joanna Smith (2021), Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre (RCCC)

For more information please contact: