Categories

Gender in early warning and early action: why do we still need to talk about it?

Why gender matters

The discussion about gender and disasters has been ongoing for decades. Unfortunately, the scale of the challenge – ensuring that a person's gender doesn’t impact how they are able to respond to, and recover from, a disaster – means that this discussion is likely to continue for decades to come.

In all contexts around the world, gendered inequalities and norms play out in terms of household roles, access to resources, power, workloads, livelihoods and more. There are structural and normative barriers to gender inclusion, and different expectations and access to resources and decision making between men and boys, women and girls, and people of other marginalized gender groups. These result in different disaster impacts for women, girls, and other genders. The more unequal a community or society is, the worse women, girls and other gender minorities fare during a disaster.

How does this manifest in early warning and early action?

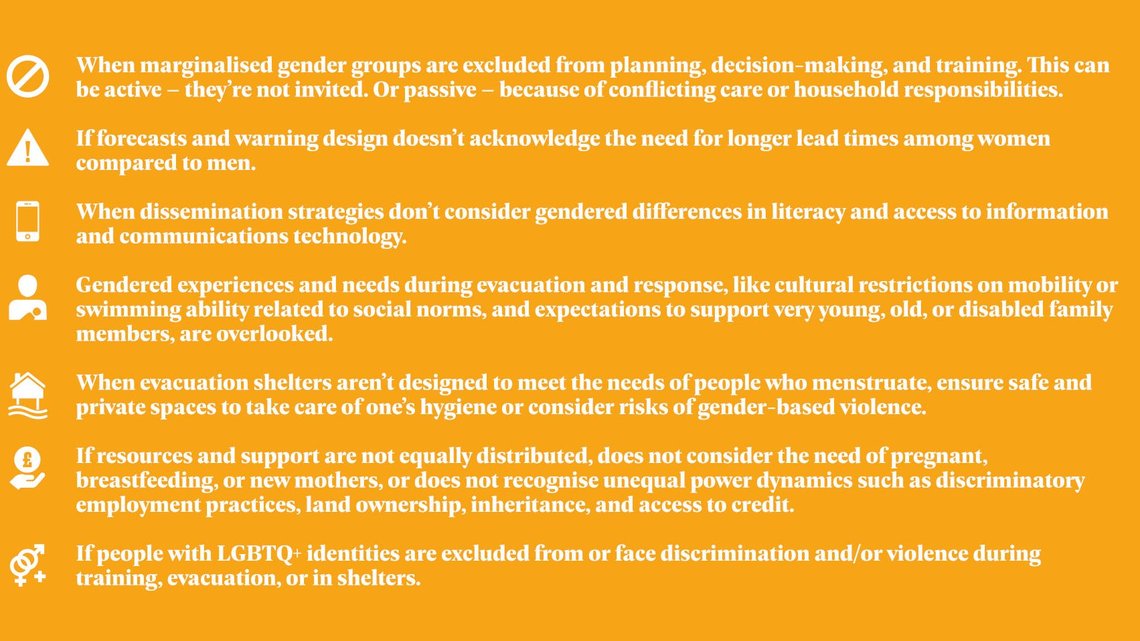

Gendered inequalities show up as barriers and challenges across all areas of early-warning systems and forecast-based early action, as the following figure shows.

Not considering gender differences in roles and responsibilities can also mean opportunities are missed, such as not utilizing women-led community support groups and/or informal dissemination networks. Marginalized gender groups have an important capacity and valuable perspectives in terms of finding new solutions and innovations. And we know, from bitter experience, that early warnings and early actions that do not actively consider and integrate gendered needs and experiences will harm marginalized gender groups.

If there is evidence that gender matters, why is there still a problem?

Lack of awareness and understanding of gender

‘We don’t have a gender problem here, we are very friendly.’

There is a need to proactively consider gender inequalities and differential impacts from disasters when designing early warnings and early actions, but awareness and recognition of this remains inconsistent. In many cases, people are uninformed or lack an understanding of gender inequalities, even in the contexts where they work or live.

This can be especially true for people in positions of power, who have not directly experienced inequalities themselves. This ‘gender blind’ perspective refuses to acknowledge how people can be oppressed or privileged because of their gender identity. Also, it is important to remember that LGBTQ+ people exist everywhere, even if they are not openly disclosing their identity.

Nor is everyone in the same place in terms of understanding gender beyond the binary (women/men). The needs and experience of cis women and girls have been, and will continue to be, a vital area of focus for policy-makers and practitioners within the disaster sector. Encouragingly, we are starting to see recognition that all genders are impacted by disasters, and that a binary approach to mitigating these impacts is further marginalizing already excluded and marginalized sections of society. There is quite some way to go, however.

LGBTQ+ refers to people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning and others (the ‘plus’).

Cisgender describes a person whose gender identity corresponds to their sex as assigned at birth.

Lack of ownership

‘I’m not a gender expert, I’m a technical person – considering gender is outside of my remit.’

Many people in institutional or operational roles do not consider thinking about, considering or addressing gender issues to be their responsibility. This can often be the case for those in more technical roles, or people with backgrounds in physical science. For example, in early-warning systems, those in institutional or governmental positions may place a stronger emphasis on the monitoring, forecasting and warning components. People may not understand why they need to consider gender in their technical work, especially if it has not formed part of their training or education to date.

Often, people feel like they do not have the requisite expertise, experience or knowledge to address gender considerations. There is an attitude that this responsibility is solely for the nominated gender expert within or outside the team to ‘deal with’ or ‘fix’.

A difficult and systemic issue

Challenging unequal power dynamics and social exclusion can be difficult from cultural, political and/or personal perspectives. And, difficult as it is to reach consensus on the importance of gendered approaches, actually delivering gender transformative programmes is even harder. But the status quo needs constant challenging if it’s ever going to shift; if we are not conscious in our efforts, it is really easy to slide into patterns that reinforce the power dynamics that marginalize people who are not cis-men.

An evacuation drill in Chosica, Peru. © Practical Action

An automatic rainfall station in Nepal. © Practical Action

An evacuation drill in Chosica, Peru. © Practical Action

An automatic rainfall station in Nepal. © Practical Action

What’s the solution?

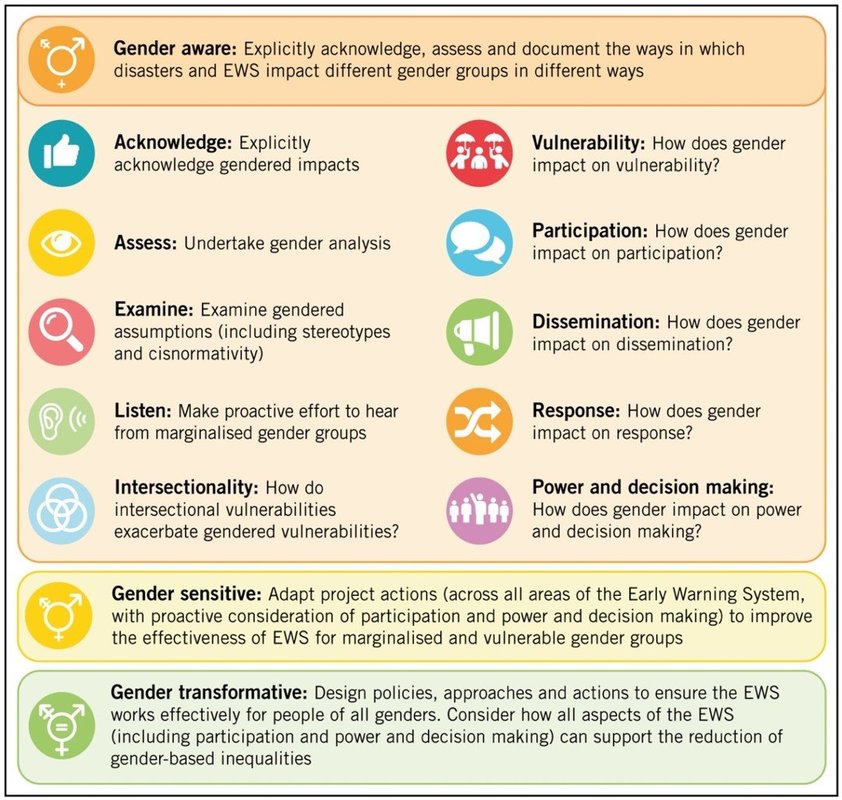

There is a need to draw on existing frameworks and evidence to change individuals, institutions and systems from being gender unaware to becoming gender sensitive, and to shift towards gender-transformative approaches when designing and implementing early-warning and early-action approaches. The figure below provides a checklist for gender-aware, sensitive and transformative practices (Brown et al. 2019).

It is necessary to allocate the additional time needed to bring people up to speed on the evidence, and ensure their understanding and awareness of the different barriers, issues and needs related to gender and marginalization. There is also a need to shift away from the idea that this is the responsibility of a select few, and help other stakeholders take responsibility and develop programmes and plans that are based on an understanding of differentiated gendered needs. Without this, any gendered considerations in the design of interventions will be ineffective and/or unlikely to be implemented by disengaged stakeholders.

The tools and approaches used in the study are unique and have allowed us to understand vulnerability and marginalization in Baguio City, in a really meaningful way.

Recognizing that gender differences are always present, and everywhere in the world, requires us to keep talking, sharing and learning. We have an obligation to listen to those with different experiences and proactively reach out to hear from gender-diverse groups. This is an ongoing process and it is necessary to reflect, continually and critically, and adapt to an ever-changing societal environment.

It is essential to consider the impacts of gender and social inclusion from the start, and develop actions that specifically address the needs of the most vulnerable, rather than a perceived majority. Only by doing so will early warnings and early actions be effective for everyone who needs them, leave no one behind, and support equitable and inclusive risk-reduction and resilience.

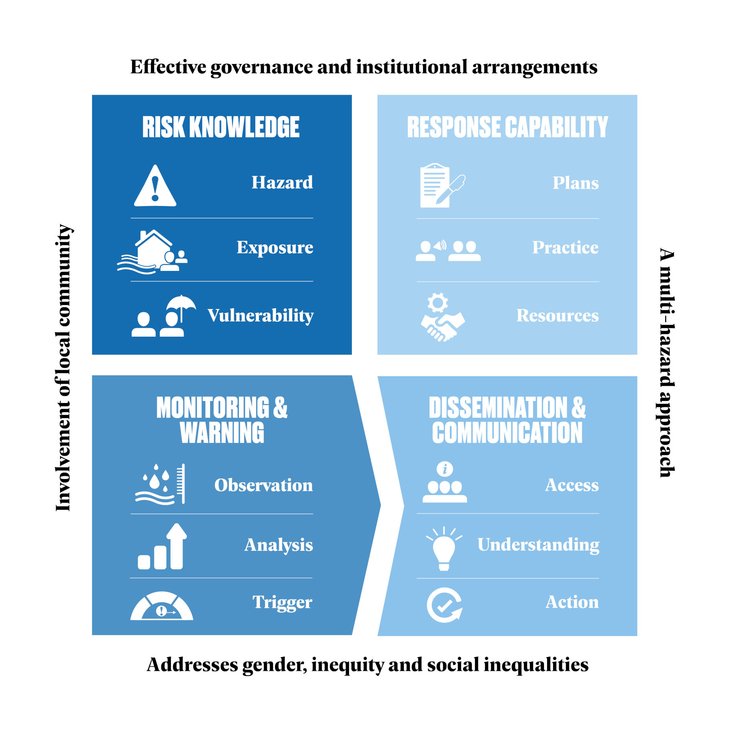

Practical Action's updated diagram of early-warning systems

This updated diagram of an early-warning system, by Practical Action, replaces the label ‘Consideration of gender perspectives and cultural diversity’ with ‘Addresses gender, inequity and social inequalities’ along its bottom axis. This reflects new evidence and the changed discourse since the original diagram was published (Brown et al., 2019). In particular, Practical Action has reflected that the original phrasing can be problematic if ‘considering cultural diversity’ is interpreted as working to uphold traditional norms and structures that don’t serve everyone; a more reflective perspective is needed to actively consider whether those cultural practices are enforcing harmful social inequalities that need to be addressed, in order to establish effective early-warning systems for everyone.

The suggested citation for this diagram is: Practical Action, 2023, Early Warning System Diagram.

This blog was written by Mirianna Budimir, Anna Svensson, George Williams (all Practical Action), Kevin Blanchard (DRR Dynamics), Audrey Oettli (IFRC) and Dorothy Heinrich (Anticipation Hub).

The views noted under the section ‘If there is evidence that gender matters, why is there still a problem?’ are not direct quotes, but capture some of the common perceptions shared about around this theme.

Further resources

- Aiming for inclusive early warning systems

- Gender equality in the context of multi-hazard early warning systems and disaster risk reduction

- Gender Transformative Early Warning Systems

- Gender and age inequality of disaster risk

- GESI FEWS in Baguio City

- Unseen, unheard: Gender-based violence in disasters

- Research Query: GBV and Anticipatory Action Approaches, GBV AoR (2021)

- Research Brief: Climate Change and Gender-Based Violence- What are the links?, GBV AoR. (2021)

- The Gender Handbook for Humanitarian Action, IASC

- LGBTQIA+ People and Disasters